The following is a conversation with Dr. Amy Welsh about her background and her perspective on the sensational dire wolf story.

Dr. Amy Welsh Q&A

West Virginia University School of Natural Resources and the Environment

Dr. Amy Welsh will give a virtual presentation at the upcoming Café Sci event on Mon., July 7 at 7 p.m. As a professor in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources Department at West Virginia University, her work in conservation genetics is extensive and has covered many different species.

Based on her immense knowledge and expertise, Dr. Welsh will weigh in on the recent dire wolf resurrection phenomenon. The following is a conversation with Dr. Welsh about her background and her expert perspective on the sensational dire wolf story.

Conversation edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: What is your research focus, how did you become involved in it, and how does it connect to the talk you’ll be giving at Café Sci?

A: I took a winding path to get here. I studied zoology and psychology at the University of Maryland, then worked on sleep deprivation research for the military –completely different from what I do now. I later pursued a master’s in forensics at George Washington University, initially aiming for forensic psychology. But I quickly realized most jobs were in DNA analysis, so I pivoted.

During my master’s, I interned at the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Lab in Oregon, where I discovered conservation genetics – using DNA to protect wildlife. After graduating, I worked in human genetics, identifying remains of soldiers from past wars. It was meaningful work, but I found forensics emotionally heavy and wanted to return to my passion: conservation.

That led me to a Ph.D. at UC Davis studying Lake Sturgeon genetics. Since 2011, I’ve been at West Virginia University in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources Program. My lab works on a wide range of species – fish, mammals, amphibians, birds – you name it.

My Café Sci talk is about de-extinction and dire wolves. I used to mention de-extinction briefly in class, thinking it was pure sci-fi. But over the years, it’s become a real possibility, and it’s been fascinating to watch that shift.

Q: Tell us more about what your Café Sci lecture will explore.

A: My talk will look at where conservation genetics has been and where it’s headed. I’ll start with some background on the field, then dive into the controversy around de-extinction – especially using dire wolves as a case study.

Dire wolves make for great headlines, but the science and ethics are complex. Should we bring back extinct species, or focus on saving those that are still here but struggling? There’s concern that if people think extinction is reversible, they might deprioritize conservation.

We only have two dire wolves, which isn’t enough for a population, while species like gray wolves are still in trouble. But the technology behind de-extinction has real conservation value. For example, scientists cloned a stallion from the 1980s to boost genetic diversity in the endangered Przewalski’s horse population. It’s not as flashy as bringing back an extinct species, but it’s a powerful tool.

I’ll also touch on the debate over whether the revived dire wolf is truly a dire wolf – since only certain genes were targeted, and there’s more to an organism than just its DNA. I’m excited to explore these questions and hear what the Café Sci audience thinks.

Q: In the scientific community, there’s debate around the ethics of conservation genetics and de-extinction. What are some of the most compelling arguments you’ve heard?

A: These conversations are happening more often now, which is exciting because the science is becoming real. Many of us feel torn – we’re amazed by what’s possible, like the dire wolf story, but also question the priorities. With so many urgent conservation issues, should we be putting resources into bringing back extinct species?

There’s a lot of enthusiasm for the technology and its potential. Stories like the dire wolves can help generate funding and public interest, which is great. But there’s concern too – should de-extinction be the focus, or should we use these tools to help species that are still here?

There’s also the “Jurassic Park” question: if we start cloning extinct species, could things spiral out of control? And even scientifically, what makes a true dire wolf? If we’re only targeting certain genes, are we really bringing the species back?

Q: You mentioned there’s more to an organism than its genetics, and there’s debate over whether these dire wolves are truly dire wolves. What’s your perspective?

A: It really depends on how you define a species – and there are many definitions. From an ecological standpoint, are they filling the same role in the environment? If not, maybe they’re not the same species.

There’s also the microbiome to consider. The microbes living in an organism are shaped by its environment and diet, which can affect gene expression. Today’s dire wolves would have a very different microbiome than their ancient counterparts.

Plus, the genetic work focused on a narrow set of genes. If we’re defining a species based on just a few markers, is that really enough? It raises important questions about which species concept we’re using and whether it’s the right one for this kind of work.

Q: How do you see climate change affecting your research in conservation genetics?

A: I’m hopeful about how emerging technologies can help species adapt to climate change. There’s a lot of research identifying genes that improve climate resilience – like heat tolerance in fish. In the past, we could identify those genes but had to rely on natural selection, which can be too slow to save a species.

Now, with gene editing tools like those used in the dire wolf project, we might be able to give populations a genetic boost before it’s too late. The same goes for disease resistance – if we can insert beneficial genes directly, we could speed up adaptation and potentially save species.

Of course, there are risks. We don’t always know what else those genes might affect, and there’s a bit of that “Frankenstein” fear. But in the face of rapid climate change, these tools could be critical for survival.

Q: As an average citizen, what steps can people take to help wildlife in their communities, especially where biodiversity is declining?

A: The biggest threat to species is still habitat loss and degradation. So, the most impactful thing people can do is help preserve or restore habitats.

Even with advanced tools like de-extinction or genetic modification, if there’s no habitat for these animals, they won’t survive. It all comes back to protecting the places they live.

Supporting habitat conservation, restoring natural areas, and improving connectivity between fragmented habitats are key. Isolated populations struggle to adapt, especially with climate change, so keeping habitats connected is critical for long-term survival.

Q: Media stories about de-extinction can be exciting, but also controversial. How can the public engage with these stories in a more informed way?

A: Sometimes the headline is fine – it gets people excited about science and conservation. But the concern is when people think we no longer need to protect existing species because we can just bring them back.

It’s important to understand that two dire wolves don’t make a population. Even if we tried to build one, we’d face issues like the Founder Effect, where limited genetic diversity can cause long-term problems.

The technology is exciting and can inspire interest and funding, but it’s not a substitute for real conservation work. We still need to protect habitats and species that are here now.

Dr. Amy Welsh Q&A

West Virginia University School of Natural Resources and the Environment

Dr. Amy Welsh will give a virtual presentation at the upcoming Café Sci event on Mon., July 7 at 7 p.m. As a professor in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources Department at West Virginia University, her work in conservation genetics is extensive and has covered many different species.

Based on her immense knowledge and expertise, Dr. Welsh will weigh in on the recent dire wolf resurrection phenomenon. The following is a conversation with Dr. Welsh about her background and her expert perspective on the sensational dire wolf story.

Conversation edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: What is your research focus, how did you become involved in it, and how does it connect to the talk you’ll be giving at Café Sci?

A: I took a winding path to get here. I studied zoology and psychology at the University of Maryland, then worked on sleep deprivation research for the military –completely different from what I do now. I later pursued a master’s in forensics at George Washington University, initially aiming for forensic psychology. But I quickly realized most jobs were in DNA analysis, so I pivoted.

During my master’s, I interned at the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Lab in Oregon, where I discovered conservation genetics – using DNA to protect wildlife. After graduating, I worked in human genetics, identifying remains of soldiers from past wars. It was meaningful work, but I found forensics emotionally heavy and wanted to return to my passion: conservation.

That led me to a Ph.D. at UC Davis studying Lake Sturgeon genetics. Since 2011, I’ve been at West Virginia University in the Wildlife and Fisheries Resources Program. My lab works on a wide range of species – fish, mammals, amphibians, birds – you name it.

My Café Sci talk is about de-extinction and dire wolves. I used to mention de-extinction briefly in class, thinking it was pure sci-fi. But over the years, it’s become a real possibility, and it’s been fascinating to watch that shift.

Q: Tell us more about what your Café Sci lecture will explore.

A: My talk will look at where conservation genetics has been and where it’s headed. I’ll start with some background on the field, then dive into the controversy around de-extinction – especially using dire wolves as a case study.

Dire wolves make for great headlines, but the science and ethics are complex. Should we bring back extinct species, or focus on saving those that are still here but struggling? There’s concern that if people think extinction is reversible, they might deprioritize conservation.

We only have two dire wolves, which isn’t enough for a population, while species like gray wolves are still in trouble. But the technology behind de-extinction has real conservation value. For example, scientists cloned a stallion from the 1980s to boost genetic diversity in the endangered Przewalski’s horse population. It’s not as flashy as bringing back an extinct species, but it’s a powerful tool.

I’ll also touch on the debate over whether the revived dire wolf is truly a dire wolf – since only certain genes were targeted, and there’s more to an organism than just its DNA. I’m excited to explore these questions and hear what the Café Sci audience thinks.

Q: In the scientific community, there’s debate around the ethics of conservation genetics and de-extinction. What are some of the most compelling arguments you’ve heard?

A: These conversations are happening more often now, which is exciting because the science is becoming real. Many of us feel torn – we’re amazed by what’s possible, like the dire wolf story, but also question the priorities. With so many urgent conservation issues, should we be putting resources into bringing back extinct species?

There’s a lot of enthusiasm for the technology and its potential. Stories like the dire wolves can help generate funding and public interest, which is great. But there’s concern too – should de-extinction be the focus, or should we use these tools to help species that are still here?

There’s also the “Jurassic Park” question: if we start cloning extinct species, could things spiral out of control? And even scientifically, what makes a true dire wolf? If we’re only targeting certain genes, are we really bringing the species back?

Q: You mentioned there’s more to an organism than its genetics, and there’s debate over whether these dire wolves are truly dire wolves. What’s your perspective?

A: It really depends on how you define a species – and there are many definitions. From an ecological standpoint, are they filling the same role in the environment? If not, maybe they’re not the same species.

There’s also the microbiome to consider. The microbes living in an organism are shaped by its environment and diet, which can affect gene expression. Today’s dire wolves would have a very different microbiome than their ancient counterparts.

Plus, the genetic work focused on a narrow set of genes. If we’re defining a species based on just a few markers, is that really enough? It raises important questions about which species concept we’re using and whether it’s the right one for this kind of work.

Q: How do you see climate change affecting your research in conservation genetics?

A: I’m hopeful about how emerging technologies can help species adapt to climate change. There’s a lot of research identifying genes that improve climate resilience – like heat tolerance in fish. In the past, we could identify those genes but had to rely on natural selection, which can be too slow to save a species.

Now, with gene editing tools like those used in the dire wolf project, we might be able to give populations a genetic boost before it’s too late. The same goes for disease resistance – if we can insert beneficial genes directly, we could speed up adaptation and potentially save species.

Of course, there are risks. We don’t always know what else those genes might affect, and there’s a bit of that “Frankenstein” fear. But in the face of rapid climate change, these tools could be critical for survival.

Q: As an average citizen, what steps can people take to help wildlife in their communities, especially where biodiversity is declining?

A: The biggest threat to species is still habitat loss and degradation. So, the most impactful thing people can do is help preserve or restore habitats.

Even with advanced tools like de-extinction or genetic modification, if there’s no habitat for these animals, they won’t survive. It all comes back to protecting the places they live.

Supporting habitat conservation, restoring natural areas, and improving connectivity between fragmented habitats are key. Isolated populations struggle to adapt, especially with climate change, so keeping habitats connected is critical for long-term survival.

Q: Media stories about de-extinction can be exciting, but also controversial. How can the public engage with these stories in a more informed way?

A: Sometimes the headline is fine – it gets people excited about science and conservation. But the concern is when people think we no longer need to protect existing species because we can just bring them back.

It’s important to understand that two dire wolves don’t make a population. Even if we tried to build one, we’d face issues like the Founder Effect, where limited genetic diversity can cause long-term problems.

The technology is exciting and can inspire interest and funding, but it’s not a substitute for real conservation work. We still need to protect habitats and species that are here now.

To stay updated on the latest science news from Carnegie Science Center, make sure to sign up ![]() to receive updates and never miss science news.

to receive updates and never miss science news.

Stargazing: Pluto Anniversary – New Definition of a Planet

A small icy world at the outer reaches of our solar system revolved as the center of attention and consternation on August 24, 2006. The subject of that year’s gathering of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) would bring professional astronomers and science...

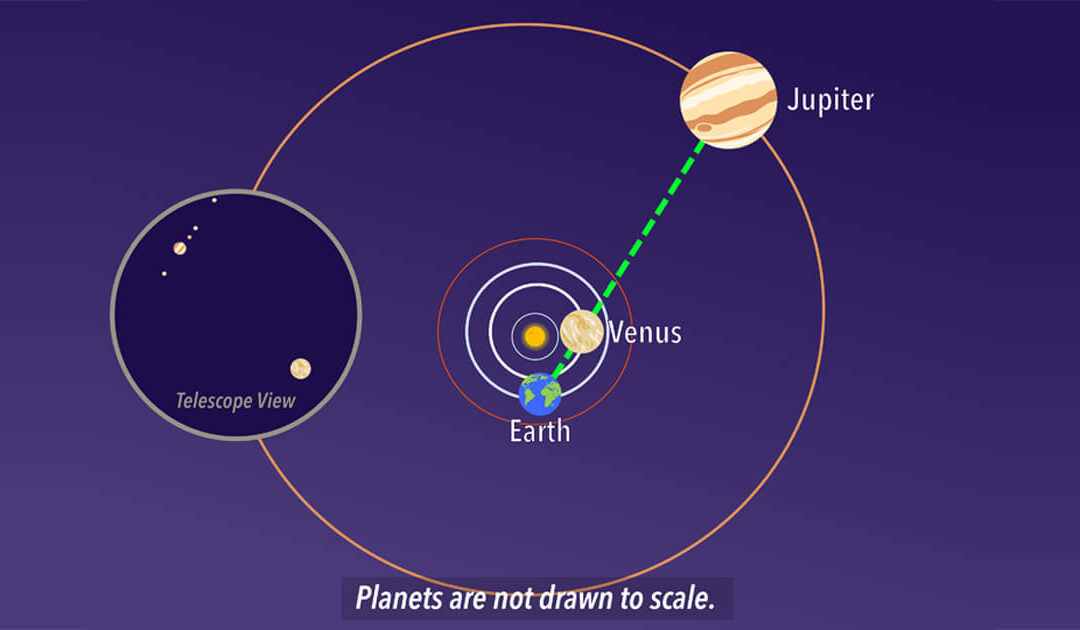

Stargazing: Perseids and Venus-Jupiter Conjunction

This time of year is usually the moment to break out the lawn chairs for the annual spectacle of the Perseid meteor shower. Home > Blog ...

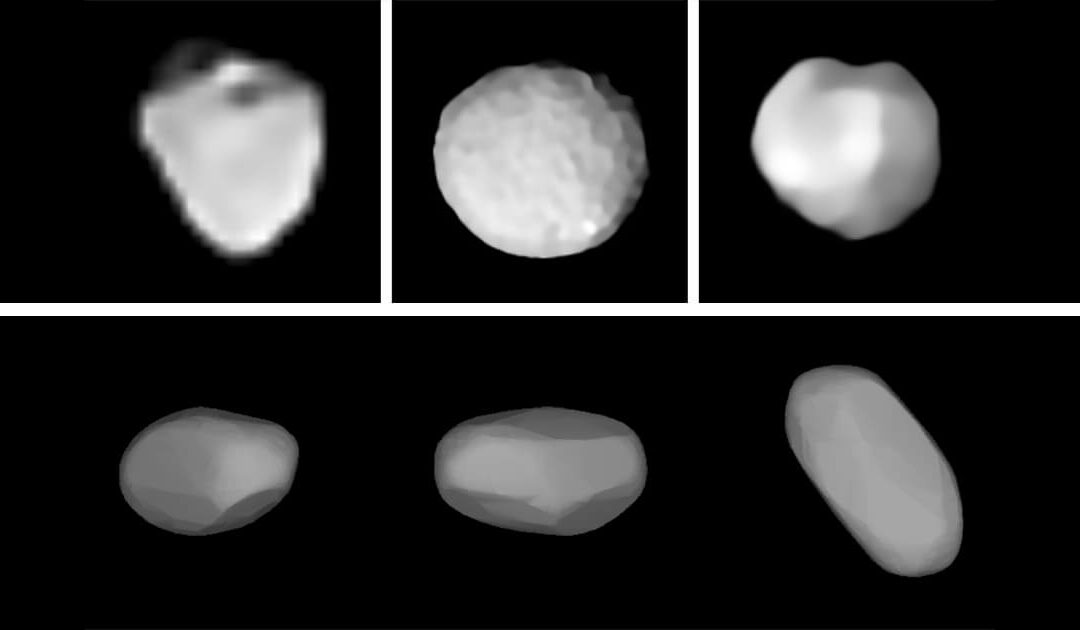

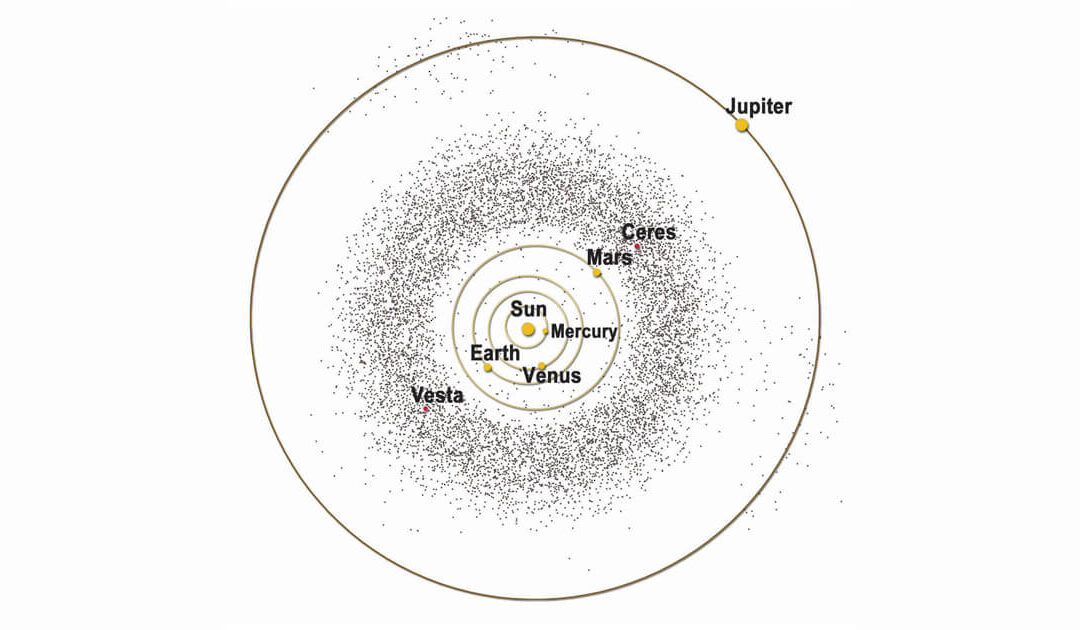

Stargazing: August Asteroids

Several large asteroids will have their brightest showings of the year through August. Home > Blog Between the planetary orbits...

Stargazing: Crescent Moon by Spica

On the evening of July 30, one of the bluest stars in the sky will gleam just above the waxing crescent moon. Spica is a blue giant star and the brightest in the constellation Virgo. Home > Blog [acf...

Stargazing: Scorpius

Soaring through July skies is an ancient arachnid known for its sting. Scorpius the Scorpion, with its distinctive curved spine and stinger poised to strike, holds a large profile low to the southern horizon. Its Latin name translates to the “creature with the...

Stargazing: Vega – Anniversary of First Photo of Star Taken

On July 17th, 1850, the first photograph of a star other than our Sun was taken. Home > Blog Brilliant Vega is the brightest...

Dr. Doug Henry Q&A

The following is a conversation with Dr. Henry about working in the mental health field and tips on improving mental health every day. Home > Blog Dr. Doug Henry Q&A Vice President and Medical Director,...

Stargazing: Pittsburgh Goes to the Moon

This year celebrates the 56th anniversary of the first moon landing. On July 20, the world watched as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped onto the surface of the moon. Home > Blog [sv...

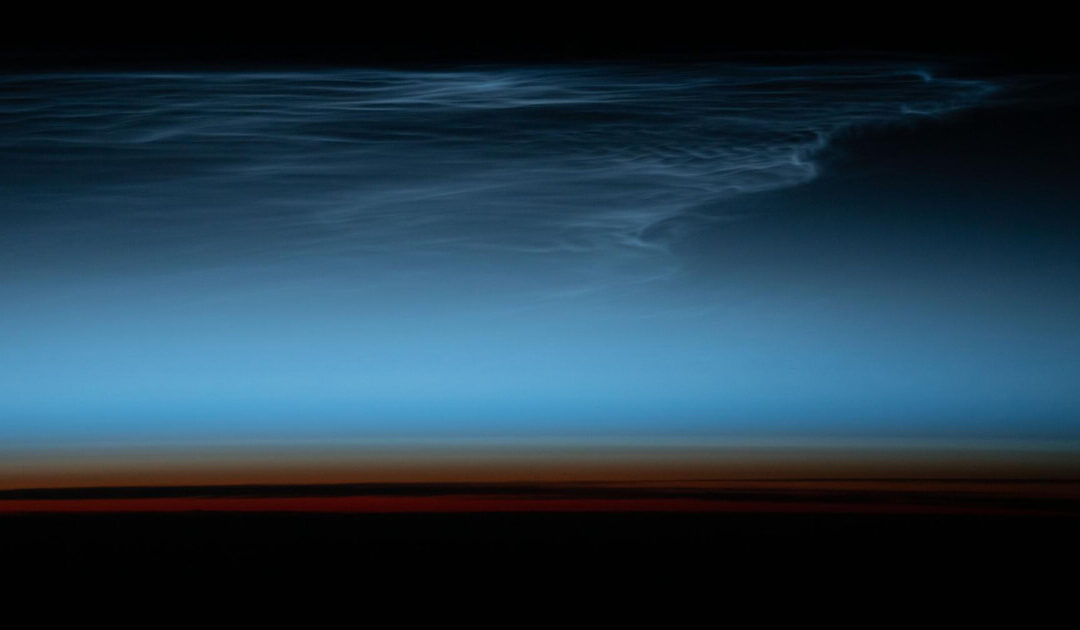

Stargazing: Noctilucent Clouds

Summer is the season to spot rare and luminescent Noctilucent Clouds. From May to early August, these ethereal clouds show their best displays thirty minutes after sunset or before sunrise. Home > Blog [acf...

Stargazing: June 30 Asteroid Day – date of Siberian Tunguska Event

Pre-dawn hours of June 27 will bring peak opportunities to view June’s Bootid meteor shower. A thin crescent moon will enhance the chances of seeing meteors flash across the sky. Home > Blog ...